When you think of Iowa, let’s be real, you don’t think of a state that’s filled with Black people.

In fact, the most recent U.S. Census data shows that Iowa ranks in the top 10 of the Whitest states in the country where an estimated 90 percent identify as Caucasian.

It’s been this way for longer than most of us have been alive but there was a point in the state’s more than 170-year history when there was a predominantly Black town thriving on the level of Tulsa, Oklahoma and Durham, North Carolina’s Parrish Street – just to name a few.

“I couldn’t believe such a town existed here, literally in the middle of farmland in rural Iowa in the 1900s,” Rachelle Chase, author and Executive Director of the organization UnitingThrough History, recalls when she first discovered the town’s history.

Chase’s organization was founded in 2021, but she’s been working tirelessly over the last decade researching the Black history in Iowa while creating opportunities for people to learn and explore this history.

“What’s fascinating to me is during this time, the state was 99.3 percent White, yet you’ve got this town, that is the largest unincorporated town in Iowa with an estimated population of about 5,000 residents in its heyday, where 40 to 55 percent of the population was Black for most of his time,” says Chase.

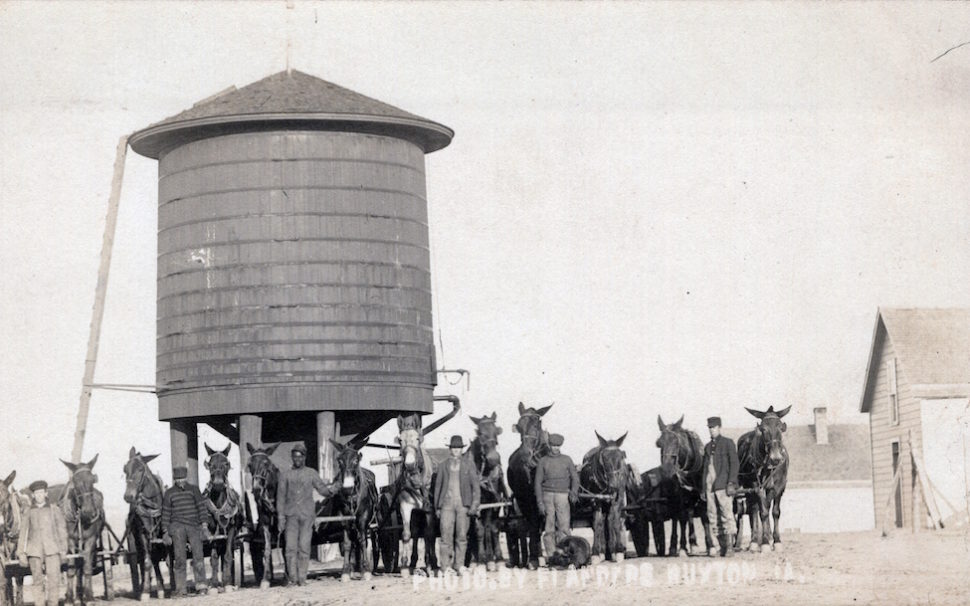

Located in the Southeastern region of the Hawkeye State, Buxton was founded in 1873 by The Consolidation Coal Company. It was a period in time when coal mining was a popular and great way to earn a living. By 1905, state historians estimate the town boasted 2,700 African Americans and a little more than 1,900 Whites.

And while Buxton was founded by a corporation to support an economic boom attributed directly to both the coal mining and railroad industries, Black people thrived on a whole different level outside of what Chase calls racist economic industries.

“You’ve got this town where Black people are leaders in this community,” Chase adds. “You’ve got doctors, lawyers, and business owners. There were at least three hotels owned by Black people, numerous restaurants, grocery stores, and pharmacists. There wasn’t a police force, so, you had Black justices of the peace or serving in constables.”

Nearly 10 years following the start of Jim Crow laws – which some scholars believe began as early as 1865 immediately after the ratification of the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery in the United States – is a town where Black people are successfully intertwining their everyday lives with White people.

Buxton was indeed a juxtaposition of Black people being treated fairly and equally yet, everywhere else in the country considered Blacks as less than and reminded them every day.

“There was a Black doctor, Dr. E.A. Carter, who was one of the first doctors and first Black man to graduate from the University of Iowa. He graduated top of his class, moved to Buxton, and was known for delivering White babies in Buxton when [Black] men across the country were being lynched for just talking or bumping into White people.”

According to Chase, Black people even received support from state leaders. She says this is one of the stark differences between communities burned down such as Tulsa.

“There was never a Tulsa kind of situation because this was a corporation who was bringing in big revenue to this community, which means they had the backing of the state. There was no way this would have been another Tulsa situation because there was no way the company would have tolerated outsiders coming in and disrupting the business,” she adds.

By the 1920s, the once successful mining community became a ghost town. Just a few years prior, the demand for coal started to dwindle and the major players decided on moving operations to other places to pay less in taxes. Residents left to seek better economic opportunities, including Black people who began leaving the area around 1911. White people were the majority by 1915.

In 1919, the town’s population fell to 400 and the last coal mine reportedly closed in 1927.

There are a few structures that still stand today in the midst of cornfields and trees as ruins. While a majority of the physical structures were torn down, Chase doesn’t want the history or spirit of Buxton to be obliterated.

“Buxton is a place that teaches us something still relevant to this day. It serves as a reminder of how successful a town can be when you have leadership saying, ‘We’re going to create an environment of equal opportunity and equal access where people can have a good life and make a good living.’”